Art, Wildfire, and Innovation with Professor Emily Schlickman

The 2023 Environmental Faculty Fellow discusses her work's unique intersections

Quick Summary

- UC Davis assistant professor and 2023 Institute of the Environment Faculty Fellow Emily Schlickman talks beneficial fire, the latest in fire-resilient design, an upcoming exhibition at the Manetti Shrem Museum, and how we might better live with wildfire.

One doesn’t often find art, design, and wildfire discussed in the same sentence, but Emily Schlickman, a UC Davis assistant professor of landscape architecture and environmental design and 2023 Institute of the Environment Faculty Fellow, takes all three and combines them with community and climate change resilience to advance our understanding of wildfire and envision how we may better manage its impacts on the planet.

Schlickman’s research explores how to bolster resilience in wildfire-prone areas through landscape stewardship and community design techniques, and she recently volunteered to take part in the Yolo County Prescribed Burn Association’s first demonstration prescribed burn on June 17. Schlickman also has an upcoming exhibition on the transformative nature of fire planned at the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, as well as a book discussing the design challenges of wildfire. Check out Design by Fire: Resistance, Co-Creation, and Retreat in the Pyrocene, and purchase a copy here.

She spoke with the Institute about the connections between all the different facets of her work:

How did you get involved with the Prescribed Burn Association (PBA) and Yolo County Resources Conservation District (RCD)?

Jullianne Ballou, associate director of strategic initiatives at the Institute of the Environment, introduced me to a few folks at the RCD and their newly formed PBA. She knew I had an interest in wildfire adaptation with my work as an Environmental Faculty Fellow and thought I might want to collaborate with them.

It was very serendipitous timing, actually, as I had just completed all of my basic wildland firefighter training (which is often needed when conducting prescribed burns). Jullianne introduced me on June 1, and just over two weeks later, I joined them for their first prescribed burn in Yolo County, just north of the community of Capay.

Over the course of the burn, I witnessed fire behavior I had never seen before, including bouts of headfire, where flames burned with the prevailing wind, as well as a number of fire whirls, with embers spinning in vortex columns across the landscape.

What was your experience like during the prescribed burn on June 17?

The experience was really eye-opening for me.

After checking in with all of my personal protective equipment in tow – long-sleeved Nomex pants and shirt, leather boots, leather gloves, a helmet, and goggles – we had a briefing to go over safety protocols, group assignments, the communication plan, the operation map, and the medical plan in the case that any injuries occurred during the burn. We also spent time discussing the primary objectives for the burn, which included invasive weed management and building prescribed fire capacity in the county for wildfire resilience. For the briefing, there were about 60 of us gathered around topographic maps of the 27-acre burn unit, with markers showing drop points, tank locations, and control lines.

After receiving my burn assignment in the holding group, I met with our group supervisor and hand crew leader to go over how we would confine the fire to its predetermined burn area and oversee post-burn mop-up operations.

The firing group ran a test ignition by lighting a small area of barbed goatgrass and yellow starthistle on fire using their drip torches. After the initial burn went as planned, they began running lines downslope, creating a slow backburn along the hillside. As the fire crept its way down the hill, we slowly followed it. We were instructed to look out over the surrounding landscape for any wayward embers or hotspots.

Over the course of the burn, I witnessed fire behavior I had never seen before, including bouts of headfire, where flames burned with the prevailing wind, as well as a number of fire whirls, with embers spinning in vortex columns across the landscape. I was also able to speak with so many seasoned fire professionals about what we were experiencing. Through that, I learned about things like the ecological benefits of a slow, cool burn, how public perceptions of prescribed burning are changing, and how to interpret probability of ignition readings that were coming in over the two-way radios.

After a few hours, the flame front burned out and we were left with a blackened, smoldering landscape. At that point, my handcrew worked around the perimeter of the unit doing mop-up. If we noticed any smoke coming up from the ground, we first did a “cow patty two-step” to smother any burning material and then followed up by spraying the area with a hose.

How does the project, as well as training to become a wildland firefighter, align with your research?

Over the past few decades, the movement to bring beneficial fire back to the landscape has grown, yet a number of obstacles are still making wide-scale implementation difficult. One challenge relates to public optics about beneficial fire, as many people are concerned about runaway events and increased smoke. Another challenge is that there is a shortage of qualified personnel equipped to organize and conduct the burns.

So, by training to become a wildland firefighter, participating in community-based prescribed fire activities, and documenting the experience through a range of media, I hope to better understand how cooperative burning practices can change perceptions about landscape care and increase adaptive capacity. In doing this, I hope to create mutually beneficial partnerships with fire stewardship organizations, support experiential learning, elevate indigenous knowledge and cultural sovereignty, co-create with community, and support practices that have social and ecological benefits.

What design trends are you seeing in the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI)? Any designs in particular that stand out?

I think a lot of design innovation is happening in the WUI right now. While there is still a big emphasis on home hardening and the creation of parcel-level defensible space, people are starting to think outside the box and at a range of scales. Some WUI residents are resisting wildfires by creating earth-sheltered structures or wrapping their homes in materials like aluminized blankets. Others are banding together to strategically manage landscapes around neighborhoods through burning, thinning, mulching, and grazing. In many of these communities, managed areas are designed to have multiple functions – for example, I’ve seen areas under high voltage power lines serve as wildfire risk reduction buffers as well as spaces for community recreation. In other parts of the WUI, communities are deciding where to build (or rebuild) differently than they have in the past. They are recognizing that some locations are simply too risky for development and are using land use planning techniques to bolster resilience.

Can you tell us more about the Pyro Futures exhibition and how you see art making an impact on our response to climate change?

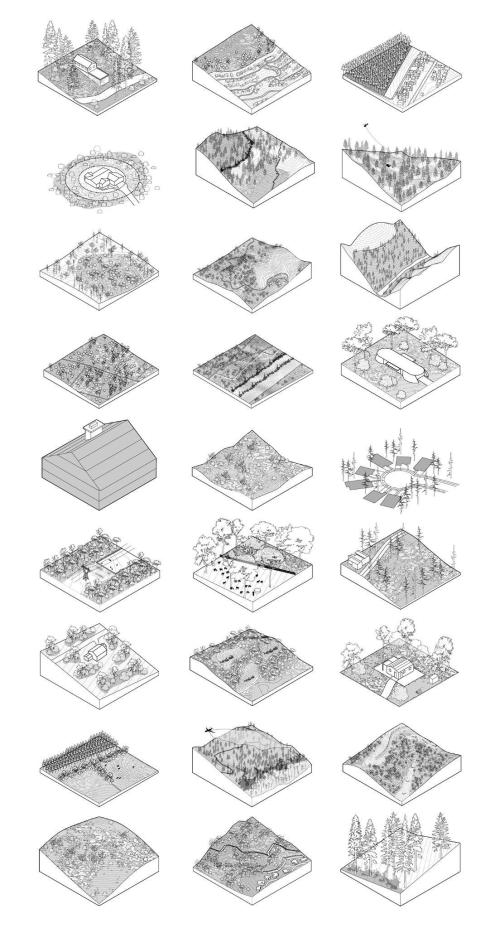

Pyro Futures is a forthcoming exhibition that my colleague Brett Milligan and I are designing and curating for the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art here on campus. The exhibition will invite collective speculation on the transformative nature of fire and the ways it can change the materiality of California’s landscapes. It will be a space that encourages participants to feel their way into possible fiery futures and our potential role in making them. The exhibition will feature large-scale aerial maps of California, imaginative time travel devices playing out a range of future scenarios, material artifacts, landscape imagery, a journaling station, a curated set of books about the Pyrocene and a wall of postcards from California’s future. (Editor's note: the exhibition will also feature aerial photos from Derek Young. Read more about some of the work Young is doing with the UC Davis Natural Reserve System here.)

Anything else you’d like to add?

If people are interested in learning more about how we might better live with wildfire, Brett Milligan and I have just publishing a book, Design by Fire: Resistance, Co-Creation, and Retreat in the Pyrocene (Routledge, August 2023), which asserts that human-altered wildfire is one of the most challenging and impactful design challenges of our times.

Structured as a series of case studies drawn from fire-prone landscapes across the world, it provides a spectrum of design and planning possibilities for communities vulnerable to wildfire: from indigenous firestick farming in Australia, to invasive plant hacking in South Africa, to silvopastoral fire flocking in Spain. Rather than serving as a book of neatly packaged solutions, it is a book of techniques to be debated, evaluated, and tested within the compounding and aggregating challenges of wildfire.

Adam Jensen is the strategic communications manager for the Institute of the Environment. He can be reached at admjensen@ucdavis.edu.